ABUSE TURNS THE WISE ONES INTO FOOLS AND ROBS THE SPIRIT OF ITS VISION

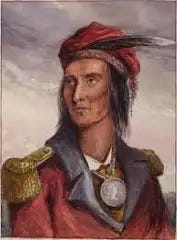

The story of Tecumseh and his death against (reportedly) Colonel Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky [future Vice President of the United States]

Today I’m rather lazy and have only gathered information to an important part of history. From my research I guess I could not have anything other than respect for Tecumseh. It might seem that Richard Johnson was truly a very brave man as well. I find sorrow in this story at many levels. The Native Americans could have lent much to our European culture if there may have been better understanding. It seems to me that we have not unlocked the shackles even now in this day and age. Abuse turns the wise one’s into fools even in these times.

ABUSE TURNS THE WISE ONES INTO FOOLS AND ROBS THE SPIRIT OF ITS VISION

Chief Tecumseh, 1768-1813 (translated as "shooting star" or "blazing comet"), led the Shawnee tribe and saw his people's lands, culture, and freedoms threatened by the aggressive white settlements. His tribe, located in the Northern Territory (the modern Great Lakes region), a Native American Confederacy was formed, led by Tecumseh, who believed that all tribes in the area needed to unite in order to preserve their heritage.

He was known by his followers as a gifted speaker with a strong voice and an eloquent orator. With his strong convictions and unyielding courage, Tecumseh led his tribe and followers in an aggressive stance against the white settlers and the United States, even to the point of fighting on the side of the British in the War of 1812. Tecumseh was killed in the Battle of Thames, and without his leadership, the confederacy he formed ceased to exist.

General Isaac Brock, who served as Commander of the British Forces at Amherstburg, poetically described Tecumseh, “A more sagacious or a gallant warrior does not, I believe, exist.”

What was the poem Chief Tecumseh wrote?

“So live your life that the fear of death can never enter your heart.

Trouble no one about their religion; respect others in their view,

and demand that they respect yours.

Love your life, perfect your life, beautify all things in your life.

Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people.

Prepare a noble death song for the day when you go over the great divide.

Always give a word or a sign of salute when meeting or passing a friend,

even a stranger, when in a lonely place.

Show respect to all people and grovel to none.

When you arise in the morning, give thanks for the food and for the joy of living.

If you see no reason for giving thanks, the fault lies only in yourself.

Abuse no one and no thing,

for abuse turns the wise ones into fools and robs the spirit of its vision.

When it comes your time to die,

be not like those whose hearts are filled with the fear of death

so that when their time comes, they weep and pray for a little more time

to live their lives over again in a different way.

Sing your death song and die like a hero going home.”

This poem has been referred to as The Indian Death Prayer, The Indian Death Poem, and even Chief Tecumseh Death Song. The poem is simply about respect and the importance of respecting yourself as well as others.

It's important to note that while these values are widely admired and associated with Chief Tecumseh, the exact origins of the poem are unclear, and it may not be a direct quote from Tecumseh himself. Nevertheless, the poem reflects principles that are consistent with many Native American cultural values.

“We do not own the land! Land is like air and water. No one owns it.”

Tecumseh

Edward Sylvester Ellis (April 11, 1840 – June 20, 1916) was an American author. Ellis was a teacher, school administrator, journalist, and the author of hundreds of books and magazine articles that he produced by his name and by a number of pen names. Notable fiction stories by Ellis include The Steam Man of the Prairies and Seth Jones, or the Captives of the Frontier. Internationally, Edward S. Ellis is probably known best for his Deerfoot novels read widely by young boys until the 1950s.

Tecumseh (c. 1768 – October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States the onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and promoting intertribal unity. Even though his efforts to unite Native Americans ended with his death in the War of 1812, he became an iconic folk hero in American, Indigenous, and Canadian popular history.

Title: Outdoor Life and Indian Stories

Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

TECUMSEH DEFIES GENERAL HARRISON

Tecumseh also believed that when war broke out between England and the United States, the former had a good chance of success. This belief he shared with the mother country herself, else she never would have begun the struggle. The Shawanoe knew that if the western tribes united to resist the Americans, they would get much better terms than if they fought separately. He bent all his energies to that difficult task.

History proves that when such an effort is set on foot, war is certain to follow. Such is the record of the past, for if union is strength, it must give that confidence which results in deeds. The activity of Tecumseh made Governor Harrison and the authorities in the West uneasy. What could be finer than the retort of the redoubtable Shawanoe, when it was asked of him:

"Why are you trying to bring about a union of the different Indian tribes?"

"For the same reason that you have brought about a union of your colonies; we never objected to that, and what business is it of yours what we do among ourselves?

Besides, it is necessary that we should unite to save us from the scoundrels among the white men."

We have no authentic record of the opinion expressed in reply to these memorable words. Probably none was given.

The bringing together in friendship of the tribes who had been enemies for centuries was a herculean task. It called into play all the matchless abilities of Tecumseh. Even he could not succeed in every instance, though it is certain none could have done so well.

In this work, the Shawanoe chieftain used the two most powerful levers that can affect the Indian mind—superstition and eloquence. The Prophet [his biological brother] was the spokesman of the former. He claimed to have had direct dealings with the Great Spirit and to utter his will. Many of his professions were grotesque to the last degree, and it may have been for that very reason that he gained hundreds of converts. Like some of the false prophets of modern days, he drew a mongrel set of disciples around him, who could be neither shamed nor argued out of their foolishness.

Tecumseh professed to believe in the supernatural power of his brother, and his example brought over many others. The master hand of the warrior could be seen in the labors of The Prophet, who began preaching about 1804. Some of his doctrines were good. He insisted that there must be a complete change in the conduct of the red children of the Great Spirit. They must quit copying the dress and manner of the white people; especially must they give up the use of ardent spirits, and all Indians must show by their lives that they were brothers and sisters. While there was impressive truth in his words about the long, happy, peaceful lives of their forefathers, such a reminder did not improve their feelings toward those who had brought about this change.

Tecumseh gave strong support to his brother in his mission. In some cases chiefs who opposed them were put to death, generally on the charge of witchcraft; in other instances, their power was taken away. While The Prophet gave all his efforts to preaching the new gospel, Tecumseh himself made a tour among the different tribes, winning many warriors and leaders to his views. That he had the encouragement of the English in this crusade cannot be denied. They saw as clearly as he that war was coming.

Now as to the real dispute between Tecumseh and the Americans; the Shawanoe insisted that no single tribe had the legal or moral right to sell to our government the lands which it might chance to occupy. Such right lay in all the tribes, whose consent was necessary in order to make such sale binding. Several large cessions had already been made and treaties signed in which these terms had been violated. Tecumseh declared that these lands belonged to the whole Indian population, that such fact should be admitted by our government and the sales cancelled, the transfer still depending upon the consent of all the tribes.

It will be seen that this view could not be accepted by our government, for if it were, there never could be any real sales, and everything that had already taken place in that respect went for nothing.

Governor Harrison of Vincennes had a delicate and hard task before him. It has been said that his government would never allow him to accept the views of Tecumseh, and he saw the time had come for plain words. He reminded the chieftain that when the white people came to take this continent, they found the Miamis occupying all the country on the Wabash, but the Shawanoes at that time lived in Georgia, from which they were driven by the Creeks. The lands had been bought from the Miamis, who were the first and real owners of it, and the only ones having a clear right to sell the lands. It was untrue to say that all the Indian tribes formed one nation, for if such had been the intention of the Great Spirit he would have given them the same language to speak, instead of so many different ones. The Miamis had thought it best for their interest to sell a part of their lands, thereby securing another annuity and the Shawanoes had no right to come from a distant country and compel the Miamis to do as the Shawanoes wished them to do.

The governor having taken his seat, the interpreter began explaining to Tecumseh what had been said by him. Before he was through, and as soon as the chieftain caught the gist of the words, he sprang to his feet in anger and exclaimed, “It is false!" His warriors leaped from the grass on which they had been sitting, and grasped their weapons. Believing he was about to be attacked, the governor drew his sword and stood ready to defend himself. He was surrounded by more of his own people than there were Indians present, but they were unarmed. They snatched up stones and clubs ready to make the best fight they could. Major Floyd, standing near the governor drew his dirk, and a Methodist minister ran to the governor's house, and, catching up a gun, placed himself in the doorway to defend the family. One of the chiefs close to the governor, cocked his pistol which he had already primed, saying, that Tecumseh had threatened his life, because he signed the treaty and sale of the disputed land. Governor Harrison told the interpreter to say to Tecumseh that he would have nothing more to do with him. He was ordered to leave, but, instead of doing so, he remained in the neighborhood with his chiefs until the next morning, when he sent an apology to the executive, pledging himself that nothing of the kind should occur again. Harrison accepted his explanation, and met him a second time. On this occasion, Tecumseh was dignified and courteous, but it was evident that he was under strong emotion. Having no new argument to offer, the plain question was put to him whether he intended to oppose the survey of the newly-bought territory. He replied that he would cling to the old boundary. The leading chiefs with him rose to their feet, one after another, and gave notice that they would stand by Tecumseh. The governor promised the Shawanoe that his words should be told to the President, but he added that it would be useless, for the land would never be given up.

Governor Harrison, hoping he could do something in a private talk, went with his interpreter to the tent of Tecumseh. He was received kindly and the two conversed for a long time, each strongly urging his views upon the other. The chieftain said he would much rather be a friend of the United States than an enemy. He knew that war between them and England would soon come, and he would greatly prefer to fight on the side of the Americans. He would do so, if his views regarding the lands were accepted.

"I repeat what I said that that will never be done, and it would be wrong in me to hold out any hope for you in that respect," replied the governor.

"Well, as the great chief in Washington is to settle the question, I hope the Great Spirit will put some sense in his head. But he is so far off he will never be harmed by the war; he can sit down and feast and drink his wine while you and I fight it out."

"Is it your determination to make war if your terms are refused?"

"It is," replied Tecumseh; "nor will I give rest to my feet, till I have united all the red men in a like resolution."

The unusual fact about these talks was the frankness with which Tecumseh gave his views. He never made the slightest effort to hide his intentions, nor would he utter any promise which he did not mean to keep. He and Governor Harrison had several interviews, but it was impossible to shake the resolution of the Shawanoe. At one of the councils, he turned to rest himself, after finishing his speech, when he saw that no chair had been placed for him. Apologizing, the governor had one hastily brought, and as it was handed to the chief, the interpreter said: "Your father requests you to take a chair."

"My father," replied Tecumseh, with dignity, "the sun is my father, and the earth is my mother; I will repose on her bosom," and he seated himself upon the ground.

Harrison finally gave over his attempt to change the views or resolution of Tecumseh. Before the final parting of the two, the governor said to him:

"We shall soon be fighting each other; a good many will be killed on both sides, and there will be much suffering; I ask you to agree with me, Tecumseh, that there shall be no capturing of women and children by your warriors, and no torture or ill treatment of such men as you may take prisoners."

"Tecumseh has never ill treated his prisoners, nor has it ever been done in his presence," was the answer of the chieftain; "why do you ask me to do that which you know I will be sure to do without the asking."

Harrison pleaded his anxiety, and thanked Tecumseh for his pledge, which he knew would be strictly kept.

The declaration of the chief that he would give his feet no rest until he united all the red men was carried out. His travels and labors were prodigious. During the year 1811, he visited numerous tribes west of the Mississippi, and about Lakes Superior and Huron, not once, but several times, thrilling all by his eloquence and winning hundreds to his side. Regarding this tour, the following incident is authentic, though since it must have been a coincidence, it certainly was one of the most remarkable ever known.

While making one of his appeals to the Creeks, Tecumseh lost patience with their coldness. He shouted angrily:

"When I go back to my people, I will stamp the ground and the earth shall shake!"

It was just about time for the chieftain to reach his towns to the north, when the New Madrid earthquake took place, the severest phenomenon of the kind which up to that time our country had ever known. When the Creeks felt the ground rocking under their feet, they ran from their tepees shouting in terror:

"Tecumseh has got home! Tecumseh has got home!"

While the chieftain was absent on this tour, The Prophet was busy with his magic. He made the wildest prophecies, and hundreds of his superstitious countrymen believed that, as he claimed, he was in direct communion with the Great Spirit. The Prophet told them the Indians should soon be given back their former hunting grounds and all the pale faces should be driven into the sea. Fired by these promises, the fanatical warriors gathered around The Prophet and began committing outrages upon the whites. The government could not refuse to go to the protection of its citizens. A small force of regulars and militia was brought together at Vincennes, the capital, and placed under the command of Governor Harrison, who was given a free hand to do all he might think necessary.

One day General Proctor was sitting on his horse calmly watching a number of Indians that were maltreating several American prisoners. Although claiming to be civilized and guided by the rules of honorable warfare, the commander smiled, as if the sight was as pleasing to him as to the dusky persecutors.

In the midst of the cruel pastime the sound of a galloping horse was heard, and the animal was reined up on his haunches within a few feet of the general. At the same instant Tecumseh leaped from his back to the ground, grasped the principal tormentor by the throat, hurled him backward a dozen feet, struck another a blow that almost fractured his skull, and with his face flaming with passion, whipped out his hunting knife, and shouted that he would kill the first one who laid hands on another prisoner.

Turning to General Proctor, he demanded with angry voice and flashing eyes:

"What do you mean by permitting such things?"

"Sir, your warriors cannot be restrained," was the reply.

With burning scorn, Tecumseh said:

"You are not fit to command; go home and put on petticoats!"

Commodore Perry won his great victory over the British fleet on Lake Erie, September 10, 1813. Had he failed, it was the plan of the British army in the West to invade Ohio. If he won, General Harrison meant to invade Canada. As soon as he learned of the victory, told to him by Perry's message, "We have met the enemy and they are ours," he lost no time in invading Canada. He embarked at Sandusky Bay, September 27, and landed near Malden. Proctor retreated to Sandwich with the Americans closely pressing him. Instead of giving battle, the British commander kept up his retreat to the Thames.

Tecumseh, with a large force of Indians, was with Proctor. He was angered over the cowardice of the British officer. The chief saw many good positions given up without a struggle, and did not hide his disgust. Going to the general he protested.

"Our fleet has gone out," said the Shawanoe; "we know they have fought; we have heard the great guns, but we know nothing of what has happened to our father with one arm. (This was an allusion to Commodore Barclay, who went into the battle of Lake Erie with only one arm and came out without that.) Our ships have gone one way, and we are much astonished to see our father tying up everything and preparing to run the other way, without letting his red children know what his intentions are. You always told us you would never draw your feet off British ground. But now, father, we see you are drawing back, and we are sorry to see our father doing so without seeing the enemy. We must compare our father's conduct to a fat dog, that carries its tail upon its back, but when frightened, it drops it between its legs and runs off.”

"Father, listen!—The Americans have not yet defeated us by land, neither are we sure they have done so by water; we therefore wish to remain here and fight our enemy, should they make their appearance. If they defeat us, we will then retreat with our father.”

"Father!—You have got the arms and ammunition which our great father sent for his red children. If you have any idea of going away, give them to us and you may go and welcome. Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit. We are determined to defend our lands, and if it be his will, we wish to leave our bones upon them."

This speech referred to the retreat from Malden. Tecumseh reluctantly gave his assent to a still further withdrawal, but he warned Proctor that if he did not stop retreating and fight, he would call off his warriors and have nothing to do with him. The British leader was forced to give battle at the Moravian Town on the Thames. He and Tecumseh chose the battle ground, the Shawanoe having the most to say about it. He showed Proctor how he could protect one flank with the river and the other with a swamp.

The battle of the Thames October 5, was another brilliant victory for the Americans under General Harrison. Proctor and a few others escaped by starting early in their flight. With this exception, the whole British force became prisoners.

Tecumseh never thought of retreating or surrendering, but, at the head of his fifteen hundred warriors, he held the American army in check for a long time. He soon received a severe wound in the arm, but paid no attention to it, and fought on with as much bravery as ever. His wonderful voice rose above the roar of battle, and nerved the arms of his warriors, but suddenly it ceased, and it quickly became known that Tecumseh had fallen. A panic instantly spread among the Indians, who broke into headlong flight in all directions.

A strange dispute raged for years as to who it was that killed Tecumseh. Although it was never settled, it is generally believed that it was Colonel Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky, afterward Vice-President of the United States. While the identity of Tecumseh's slayer may be uncertain, there is no doubt that, whoever he was, he closed the career of the "greatest American Indian that ever lived."

THE DAYS OF HEROES ARE OVER A Brief Biography of Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson DR.

DAVID PETRIELLO

Westphalia Press An Imprint of the Policy Studies Organization Washington, DC 2016

Though outnumbered two-to-one, the Kentuckians bravely slogged through the mud, debris, and shattered bodies. Col. Johnson, conspicuous atop his mount, was wounded four times, with his horse being perhaps the only thing holding him upright. It is at this point that eyewitness accounts mix with legends and campaign literature to paint a picture of what occurred next. Amidst the roar of battle the wounded Johnson spotted an Indian chief, richly adorned with his face covered in black and red lines according to some, clad only in a deer buckskin to others. Convinced that this Native was Tecumseh, or at least an important commander, Johnson spurred his horse onwards towards him. Yet in an almost comic action, as the Colonel’s horse rounded a tree it tripped and fell on an exposed root; certainly the 15 bullets discovered in the horse later didn’t improve its stability any. Though he was not seriously injured by the accident, he lost the element of surprise. Alerted to the presence of this lone rider, Tecumseh leveled his rifle and shot. The bullet struck Johnson, hitting the upper joint of his finger and continuing onward before passing through his wrist. The Indian chief then dropped his gun and gripped his tomahawk, charging at the wounded American. Col. Johnson calmly drew his own pistol and shot Tecumseh in the chest, felling the great warrior. According to oral traditions at the time, Tecumseh had a premonition of his own death in battle that day and had given away his possessions and shaken the hands of the British officers before leading his men forward.

The death of Tecumseh caused the entire Indian line to eventually crumble. After little more than 15 minutes of battle, screaming and wailing warriors fled the battlefield in a disorganized rout, loudly lamenting the loss of their leader. According to his campaign biography the badly wounded Johnson exclaimed after the killing, “the victory is ours, make the best of it.” Still others that he turned to a trusted aide and exclaimed, “I will not die. I am mightily cut to pieces, but I think my vitals have escaped.” A fellow Kentuckian later described Johnson as serene in his agony and resigned to his noble fate. He then fainted from loss of blood and had to be carried from the battlefield. Perhaps the true testament to his bravery in battle was the fact that his wounded horse also collapsed into unconsciousness before dying a few minutes later, having suffered as many injuries as its rider. Upon examination, it was claimed, Johnson’s coat held 25 bullets imbedded within it, five of which had directly injured him, most notably in the hip and thigh. As Gen. Harrison himself opined, “his numerous wounds proved his was the post of danger.”

Johnson Kills Tecumseh

Though in the end the fight lasted only 18 minutes and yielded no more than 60 casualties for the Americans and perhaps 240 for the British and Indians, it was an immense victory for the United States. Tecumseh was dead and with him the hopes of an Indian confederation in the northwest.

The Americans were once again firmly in possession of Michigan and even had a foothold in Canada. In addition, coming as it did amidst the general stalemate in the New York theater of war, the battle helped to raise American morale and relieve pressure on Madison to supply a major victory in the war. According to Richard Rush the President was overjoyed by the news, “the little President is back, and as game as ever.” It is little wonder that the battle was celebrated for years afterwards and was once described by a notable Kentucky historian as the most “Norman” of American victories.

Terrance Kirby of Kentucky confirmed this much in a letter years later to Pres. Abraham Lincoln. “I [helped] kill Tecumseh and [helped] skin him, an brot Two pieces of his yellow hide home with me to my Mother & Sweet Hart.

After the battle, American soldiers stripped and scalped Tecumseh's body. The next day, when Tecumseh's body had been positively identified, others peeled off some skin as souvenirs.The location of his remains is unknown. The earliest account stated that his body had been taken by Canadians and buried at Sadwich. Later stories said he was buried at the battlefield, or that his body was secretly removed and buried elsewhere. According to another tradition, an named Oshahwahnoo, who had fought at Moraviantown, exhumed Tecumseh's body in the 1860s and buried him on St. Anne Island on the St. Clair River. In 1931, these bones were examined. Tecumseh had broken a thighbone in a riding accident as a youth and thereafter walked with a limp, but neither thigh of this skeleton had been broken. Nevertheless, in 1941 the remains were buried on nearby Walpole Island in a ceremony honoring Tecumseh. St-Denis (2005), in a book-length investigation of the topic, concluded that Tecumseh was likely buried on the battlefield and his remains have been lost.

Initial published accounts identified Richard Mentor Johnson as having killed Tecumseh. In 1816, another account claimed a different soldier had fired the fatal shot. The matter became controversial in the 1830s when Johnson was a candidate for Vice President of the United States to Martin Van Buren. Johnson's supporters promoted him as Tecumseh's killer, employing slogans such as "Rumpsey dumpsey, rumpsey dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh." Johnson's opponents collected testimony contradicting this claim; numerous other possibilities were named. Sugden (1985) presented the evidence and argued that Johnson's claim was the strongest, though not conclusive. Johnson became Vice President in 1837, his fame largely based on his claim to have killed Tecumseh.

Tecumseh's death led to the collapse of his confederacy; except in the southern Creek War, most of his followers did little more fighting. In the negotiations that ended the War of 1812, the British attempted to honor promises made to Tecumseh by insisting upon the creation of a Native American barrier state in the Old Northwest. The Americans refused and the matter was dropped. The Treaty of Ghent (1814) called for Native American lands to be restored to their 1811 boundaries, something the United States had no intention of doing. By the end of the 1830s, the U.S. government had compelled Shawnees still living in Ohio to sign removal treaties and move west of the Mississippi River.

As I mentioned I have a bad case of the lazies today. I am uncertain what I could add to the writing above to enhance it all. I learned much in this exercise on history unknown to me. It all seemed interesting and valuable information. I assume that all persons written about were described accurately. I guess the idea of skinning the body of Tecumseh may have upset me a might. There is a lesson in knowing of this act which I hope is obvious to the reader. Thanks for reading.

206th Posting, October 8, 2024