HAVE SENSE, SPIRIT AND HONESTY ENOUGH TO SUPPORT A CONSTITUTION AGAINST TYRANNY

Recent anxiety of freedom of the press prompted this cornucopia of writing. Hope you can follow my mental intentions.

HAVE SENSE, SPIRIT AND HONESTY ENOUGH TO SUPPORT A CONSTITUTION AGAINST TYRANNY

Here we are in 2024 with Trump threatening the free press explicitly,

And it might seem that not since John Adams has anything comparable,

Visions of unhinged despots, but it might seem only so with Trump,

Each action by Adams seems that he was largely honest and only off base.

So as usual we must crack open the history books dealing with Trump,

Even though Adams probably was only overreacting to a French threat,

Now Trump is only an average fascist with designs on getting power,

So we are shocked perhaps at how far askew things have gotten,

Everyone with any sense recognizes the tyranny and the treachery.

, “Treachery has something so wicked; an open revenge would be too liberal for it”*

So are the millionaires in the media waking up a little bit now,

Perhaps their last year’s tax bill is still ruling their judgment a mite,

I guess I recognize the danger to these folks - let’s hope they do too,

Republicans have not a lick of sense in the bizarre culture of MAGA,

Indeed Trump is only following the Putin and Orban playbook,

Trump is no more original than greatly overpriced sneakers or a watch.

As we still have the vestiges of a free press - Trump must squash it,

Now was Adams also well over his skies as well back then,

Democracy can’t survive such frontal assaults - that should be obvious.

Honesty seemed important to Adams from what I can gather,

Of this Trump character who can only function in a world of dishonesty,

Now we understand that all the Trump enablers are squarely in his camp,

Every one of these verses I seem always to land on dishonest criminality,

So the average MAGA can only justify it by imagining the left is worse,

Trump is their chosen Antichrist - they seem to get a kick about it all,

Yes, the adults in the room try to steer the runaway barge of doom.

Even though we honestly question Adams from long ago - it was different,

Now the republic was very young then, experimenting as it went perhaps,

Of these days and the horrors of fascism hopefully remembered,

Understand that Milley pegged ole Donald correctly in his assessment,

Generally anyone can come to the same conclusion - but we lack stars,

Having a General say Trump is a very grave threat should count I’d think.

Trump is a very large vile of extremely deadly poison being tossed around,

Only if his foolish enablers don’t allow the poison to hit and shatter.

So he has clearly given us all the clear signs of all his intentions,

Understand that many a journalist lacks the imagination needed,

Perhaps the majority of corporate media have taken themselves out,

People who are true journalists with spines and conviction are targets,

Of the brave and professionally dedicated will be who Trump seethes over,

Regardless of Trump’s attempts I truly think there’ll be enough strength,

Today I see the delusional evangelicals are gathering for their messiah.

Authoritarian - there is a deep thirst among the masses for such a man.

Constitution has been keeping the nation glued together so far,

Of our education system which is failing us in these times,

Nothing can perhaps get through the thick skulls of so many, many,

So any enlightened or any fool can get away with whatever is their speech,

Trump can see no distinction between speech and press - he hates it all,

Indeed a professional press license seems a vital thing way past due,

Today due to the assault of Trump and MAGA truth can be a causality,

Unless America gets a firm grip - the power of lies may overtake us,

Trump can only tear at our fabric unmercifully - more stability is needed,

I am fearful for our nation now and going forward from all the bullshit,

Of those prone to believe all his lies - there is only so much we can do,

Now intuitively we know we’ll be stronger should we survive.

And will the legitimate professional journalists coalesce and fight back,

Government is rightly detached from the Fourth Estate or fourth power,

Although there are many fraudulent journalists within the mix today,

Indeed it appears that the wheels of adaptation are moving too slowly,

National cohesion is weakened from the malevolent forces at play,

So are we actually sitting ducks about to be blasted from both barrels,

Trump has proven to be the most powerful stress test we’ve encountered.

To those approving of Trump and Vance’s obvious acts as tyrants,

Yes, how could we’ve sunken so low into the acidic muck,

Reality will ultimately be recognized we reassure ourselves,

Authoritarian rule looked at with only a deep longing makes no sense,

Now we only hope that more astute minds will rule the day,

Now American democracy has been on the stove for 86,589 days so far,

Yet this cooking dish might just be thrown down the garbage disposal.

“The right of a nation to kill a tyrant, in cases of necessity, can no more be doubted, than to hang a robber, or kill a flea. But killing one tyrant only makes way for worse, unless the people have sense, spirit and honesty enough to establish and support a constitution guarded at all points against the tyranny of the one, the few, and the many.”

— John Adams

*Treachery has something so wicked and worthy of punishment in its nature, that it deserves to meet with a return of its own kind; an open revenge would be too liberal for it, and nothing matches it but itself.”

— S. Croxall.

Samuel Croxall (c. 1688/9 – 1752) was an Anglican churchman, writer and translator, particularly noted for his edition of Aesop’s Fables. Knowing the risks to which his whole poetic output exposed him, Croxall took pains to conceal his authorship both by using pseudonyms and providing false information about the work's origin. Such was the notoriety of his poetical output and the power of his named literary productions, however, that it was impossible to keep their origin hidden for long.

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of the American Revolution that achieved independence from Great Britain. During the latter part of the Revolutionary War and in the early years of the new nation, he served the U.S. government as a senior diplomat in Europe. Adams was the first person to hold the office of Vice President of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. He was a dedicated diarist and regularly corresponded with important contemporaries, including his wife and adviser Abigail Adams and his friend and political rival Thomas Jefferson.

Alien and Sedition Acts

Thomas Jefferson, Adams's vice president, attempted to undermine many of his actions as president and eventually defeated him for reelection in the 1800 presidential election.

Despite the XYZ Affair, Republican opposition persisted. Federalists accused the French and their immigrants of provoking civil unrest. In an attempt to quell the outcry, the Federalists introduced, and the Congress passed, a series of laws collectively referred to as the Alien and Sedition Acts. Passage of the Naturalization Act, the Alien Friends Act, the Alien Enemies Act and the Sedition Act all came within a period of two weeks, in what Jefferson called an "unguarded passion." The first three acts targeted immigrants, specifically French, by giving the president greater deportation authority and increasing citizenship requirements. The Sedition Act made it a crime to publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writing" against the government or its officials. Adams had not promoted any of these acts, but signed them in June 1798 at the urging of his wife and cabinet.

The administration initiated fourteen or more indictments under the Sedition Act, as well as suits against five of the six most prominent Republican newspapers. The majority of the legal actions began in 1798 and 1799, and went to trial on the eve of the 1800 presidential election. Vocal opponents of the Federalists were imprisoned or fined under the Sedition Act for criticizing the government. Among them was Congressman Matthew Lyon of Vermont,* who was sentenced to four months in jail for criticizing the President. The alien acts were not stringently enforced because Adams resisted Secretary of State Timothy Pickering’s attempts to deport aliens, although many left on their own, largely in response to the hostile environment. Republicans were outraged. Jefferson, disgusted by the acts, wrote nothing publicly but partnered with Madison to secretly draft the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. Jefferson wrote for Kentucky that states had the "natural right" to nullify any acts they deemed unconstitutional. Writing to Madison, he speculated that as a last resort the states might have to "sever ourselves from the union we so much value." Federalists reacted bitterly to the resolutions, and the acts energized and unified the Republican Party while doing little to unite the Federalists.

*Lyon had launched his own newspaper, The Scourge of Aristocracy and Repository of Important Political Truth, when the Rutland Herald refused to publish his writings. On October 1, Lyon printed an editorial which included charges that Adams had an "unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice," as well as the accusation that Adams had corrupted the Christian religion to further his war aims. Before the Alien and Sedition Acts had been passed, Lyon had also written a letter to Alden Spooner, the publisher of the Vermont Journal. In this letter, which Lyon wrote in response to criticism in the Journal, Lyon called the president "bullying," and the Senate's responses "stupid."

Once the Alien and Sedition Acts were passed, the Federalists pushed for this letter to be printed in the Vermont Journal, which Spooner did, thus adding additional charges against Lyon. One other charge included publishing letters written by the poet Joel Barlow,* which Lyon had read at political rallies. These also were published prior to the Acts. Lyon's defense was to be the unconstitutionality of the Acts, as Jeffersonians saw them as violating the First Amendment to the Constitution. In Lyon's particular case, there was the aforementioned letter to Alden Spooner as well as that of Barlow, which meant Lyon felt entitled to bring up the Constitution’s safeguards against ex post facto laws. This defense was not allowed.

Judge William Paterson lamented being unable to give a harsher punishment.

Lyon was sentenced to four months in a 16 by 12 feet (4.9 m × 3.7 m) jail cell used for felons, counterfeiters, thieves, and runaway slaves in Vergennes, and ordered to pay a $1,000 fine and court costs (equivalent to $18,317 in 2023). A bit of a resistance movement was created; the Green Mountain Boys even threatened to destroy the jail and might have done so if not for Lyon's urging peaceful resistance. While in jail, Lyon won election to the Sixth Congress by nearly doubling the votes of his closest adversary, 4,576 to 2,444. Upon his release, Lyon exclaimed to a crowd of supporters: "I am on my way to Philadelphia!”

After years of effort by his heirs, in 1840 Congress passed a bill authorizing a refund of the fine Lyon incurred under the Alien and Sedition Acts and other expenses he accrued as the result of his imprisonment, plus interest.

The First American Congress

…

On Britain still he cast a filial eye;

But sov'reign fortitude his visage bore,

To meet their legions on th' invaded shore.

Sage Franklin next arose, in awful mien,

And smil'd, unruffled, o'er th' approaching scene;

High, on his locks of age, a wreath was brac'd,

Palm of all arts, that e'er a mortal grac'd;

Beneath him lies the sceptre kings have borne,

And crowns and laurels from their temples torn.

Nash, Rutledge, Jefferson, in council great,

And Jay and Laurens op'd the rolls of fate.

The Livingstons, fair Freedom's gen'rous band,

The Lees, the Houstons, fathers of the land,

O'er climes and kingdoms turn'd their ardent eyes,

Bade all th' oppressed to speedy vengeance rise;

All pow'rs of state, in their extended plan,

Rise from consent to shield the rights of man.

Bold Wolcott urg'd the all-important cause;

With steady hand the solemn scene he draws;

Undaunted firmness with his wisdom join'd,

Nor kings nor worlds could warp his stedfast mind.

Now, graceful rising from his purple throne,

In radiant robes, immortal Hosmer shone;

Myrtles and bays his learned temples bound,

The statesman's wreath, the poet's garland crown'd:

Morals and laws expand his liberal soul,

Beam from his eyes, and in his accents roll.

But lo! an unseen hand the curtain drew,

And snatch'd the patriot from the hero's view;

Wrapp'd in the shroud of death, he sees descend

The guide of nations and the muses' friend.

Columbus dropp'd a tear. The angel's eye

Trac'd the freed spirit mounting thro' the sky.

Adams, enrag'd, a broken charter bore,

And lawless acts of ministerial pow'r;

Some injur'd right in each loose leaf appears,

A king in terrors and a land in tears;

From all the guileful plots the veil he drew,

With eye retortive look'd creation through;

Op'd the wide range of nature's boundless plan,

Trac'd all the steps of liberty and man;

Crowds rose to vengeance while his accents rung,

And Independence thunder'd from his tongue.

Barlow believed that the new country of America was a model civilization that prefigured the "uniting of all mankind in one religion, one language and one Newtonian harmonious whole" and thought of "the American Revolution as the opening skirmish of a world revolution on behalf of the rights of all humanity." An optimist, he believed that scientific and republican progress, along with religion and people's growing sense of humanity, would lead to the coming of the Millennium. For him, American civilization was world civilization. He projected that these concepts would coalesce around the rebuilding of the temple in Jerusalem.

How about a short gander at the “Sedition Act”?

FIFTH CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES:

at the Second Session,

Begun and held at the city of Philadelphia, in the state of Pennsylvania, on Monday, the thirteenth of November, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-seven.

An Act in Addition to the Act, Entitled "An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States."

SECTION 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That if any persons shall unlawfully combine or conspire together, with intent to oppose any measure or measures of the government of the United States, which are or shall be directed by proper authority, or to impede the operation of any law of the United States, or to intimidate or prevent any person holding a place or office in or under the government of the United States, from undertaking, performing or executing his trust or duty, and if any person or persons, with intent as aforesaid, shall counsel, advise or attempt to procure any insurrection, riot, unlawful assembly, or combination, whether such conspiracy, threatening, counsel, advice, or attempt shall have the proposed effect or not, he or they shall be deemed guilty of a high misdemeanor, and on conviction, before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding five thousand dollars, and by imprisonment during a term not less than six months nor exceeding five years; and further, at the discretion of the court may be holden to find sureties for his good behaviour in such sum, and for such time, as the said court may direct.

SEC. 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.

SEC. 3. And be it further enacted and declared, That if any person shall be prosecuted under this act, for the writing or publishing any libel aforesaid, it shall be lawful for the defendant, upon the trial of the cause, to give in evidence in his defence, the truth of the matter contained in publication charged as a libel. And the jury who shall try the cause, shall have a right to determine the law and the fact, under the direction of the court, as in other cases.

SEC. 4. And be it further enacted, That this act shall continue and be in force until the third day of March, one thousand eight hundred and one, and no longer: Provided, that the expiration of the act shall not prevent or defeat a prosecution and punishment of any offence against the law, during the time it shall be in force.

Jonathan Dayton, Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Theodore Sedgwick, President of the Senate pro tempore.

I Certify that this Act did originate in the Senate.

Attest, Sam. A. Otis, Secretary

APPROVED, July 14, 1798

John Adams

President of the United States.

Jonathan Dayton (October 16, 1760 – October 9, 1824) was an American Founding Father and politician from New Jersey. At 26, he was the youngest person to sign the Constitution of the United States. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1791 and later served from 1795 to 1799 as its third Speaker. He left the House in 1799 after being elected to the U. S. Senate, the where he served one term. Dayton was arrested in 1807 for alleged treason in connection with Aaron Burr’s conspiracy with to establish an independent country in the Southwestern United States and parts of Mexico. He was exonerated by a grand jury, but his national political career never recovered.

Politically, he was a staunch Federalist, believing that a strong central government was necessary to provide for the common defense, and also deeply conservative - he still wore a powdered wig long after they had fallen from fashion. As one biography puts it:

"Dayton possessed a very strong and stubborn philosophy of what was right. He believed that the government was supposed to defend the rights and freedoms of its citizens, but only when it was practical to do so. He believed in a social hierarchy supported by the government."

Hamilton and Burr were both well known to Dayton. Hamilton had been a schoolmate in Elizabethtown as well as one of the foremost Federalists, while Burr had been a fellow student at the College of New Jersey. Meeting in Philadelphia, Burr proposed a scheme which Dayton helped to finance and that purportedly intended to wrest territory in Texas from Spain and create a new western republic. Dayton was in ill health and so unable to participate directly in this filibuster, and when the plot unraveled he was charged with treason along with Burr. Although the charges were never proved and he was acquitted, his political career was finished on the national level and except for a single one year term in the New Jersey legislature he retired from public life. Shortly before his death in 1824, he entertained his old comrade-in-arms Lafayette in Elizabethtown on his grand tour of the United States.

The Framers of the Constitution were neither divinely inspired, nor infallible. There may have been giants among them (Madison, Hamilton, Franklin) but they were above all political negotiators able to craft an extraordinary, unifying document that is 220 years old today. Ben Franklin remarked during the Convention; "When a broad table is to be made, and the edges of the planks do not fit, the artist takes a little from both, and makes a good joint." Of such stuff was this nation made, and by men like Jonathan Dayton who themselves had rough edges.

Theodore Sedgwick (May 9, 1746 – January 24, 1813) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served in elected state government and as a delegate to the Continental Congress, a U.S. representative, and a senator from Massachusetts. He served as President pro tempore of the United States Senate as from June to December 1798. He also served as the fourth speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was appointed to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial in 1802 and served there for the rest of his life.

To Alexander Hamilton from Theodore Sedgwick, 10 January 1801

As to the other candidate [Jefferson] there is no disagreement as to his character. He is ambitious—selfish—profligate. His ambition is of the worst kind—it is a mere love of power, regardless of fame but as its instrument—his selfishness excludes all social %m3

affections & his profligacy unrestrained by any moral sentiment, and defying all decency. This is agreed, but then it is known that his manners are plausible, that he is dextrous in the acquisition & use of the means necessary to effect his wishes.

Nothing can be a stronger evidence of this than the situation in which he stands at this moment—without any pretention from connections, fame or services, elevated, by his own independent means, to the highest point to which all those can carry the most meritorious man in the nation. He holds to no pernicious theories, but is a mere matter-of-fact man. His very selfishness prevents his entertaining any mischievous predilections for foreign nations. The situation in which he lives has enabled him to discern and justly appreciate the benefits resulting from our commercial & other national systems; and this same selfishness will afford some security that he will not only patronize their support but their invigoration.

There are other considerations. It is very evident that the Jacobins* dislike Mr. Burr, as President—that they dread his appointment more than even that of General Pinkney.** On his part he hates them for the preference they give to his rival. He has expressed his displeasure at the publication of his letter by General Smith.*** This jealousy, and distrust, and dislike will every day more & more encrease and more & more widen the breach between them. If then Burr should be elected by the federalists agt the hearty opposition of the Jacobins the wounds mutually given & received will, probably, be incurable—each will have commited the unpardonable sin. Burr must depend on good men for his support & that support he cannot receive but by a conformity to their views.

In these circumstances then to what evils shall we expose ourselves by the choice of Burr which we should escape by the election of Jefferson? It is said that it would be more disgraceful to our country and to the principles of our government. For myself I declare I think it impossible to preserve the honor of our country or of the principles of our constitution. By a mode of election which was intended to secure to preeminent talents & virtues the first honors of our country, & forever to disgrace the barbarous institutions by which executive power is to be transmited thro’ the organs of generation, we have at one election placed at the head of our government a semi-maniac, a man who in his soberest senses is the greatest Marplot**** in nature; and at the next a feeble & false enthusiastic theorist; and a profligate without character and without property—bankrupt in both. But if there remains any thing for us, in this respect, to regard, it is with the minority in the presidential election. And can they be more disgraced than by assenting to the election of Jefferson?—the man who has proclaimed them to the world as debased in principles, and as detestable & traiterous in conduct? Burr is indeed unworthy, but the evidence of his unworthiness is neither so extensively known, nor so conclusive as that of the other man.

It must be confessed that there is ⟨a⟩ part of the character of Burr more dangerous ⟨than⟩ that of Jefferson. Give to the former a probable ⟨ch⟩ance & he would become an usurper; the latter might not incline, he certainly would not dare, to make the attempt. I do not beleive that either would succeed, & I am even confident that such a project would be rejected by Burr as visionary.

At first, I confess, I was strongly disposed to give Jefferson the preference, but the more I have reflected, the more have I been inclined to the other. Yet, however, I remain unpledged even to my friends, tho’ I beleive I shall not seperate from them.

I am ever yours, most sincerely

Theodore Sedgwick

* United States - Federalists often characterized Thomas Jefferson, who himself had intervened in the French Revolution, and his Democratic-Republican party as Jacobins. Early Federalist-leaning American newspapers during the French Revolution referred to the Democratic-Republican party as the "Jacobin Party".

** A delegate to the Constitutional Convention where he signed the Constitution of the United States, Pinckney was twice nominated by the Federalist Party as its presidential candidate in 1804 and 1808, losing both elections. A supporter of independence from Great Britain, Pinckney served in the American Revolutionary War, rising to the rank of brigadier general. After the war, he won election to the South Carolina legislature, where he and his brother Thomas represented the landed slavocracy of the South Carolina Lowcountry. An advocate of a stronger federal government, Pinckney served as a delegate to the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, which wrote a new federal constitution. Pinckney's influence helped ensure that South Carolina would ratify the United States Constitution. A town and district named Pinckneyville in South Carolina were named after Charles in 1791.

*** In March of 1785, William Stephens Smith became secretary to the American legation in London, headed by John Adams by as U.S. minister plenipotentiary to Great Britain. While residing in London, Smith courted the daughter of John and Abigail Adams, Abigail “Nabby” Amelia Adams, and the two were married in London on June 11, 1786. After almost three years of diplomacy, a frustrated John Adams ended the mission in England and the families returned to the United States in 1788 at precisely the right time for the beginnings of a new national government. In 1789, President George Washington appointed William Stephens Smith the first U.S. Marshal for the State of New York on September 26, 1789 and two years later, Supervisor of the Revenue for the District of New York. He resigned both positions after about a year in each of them in favor of the lucrative pursuit of land speculation. By 1797, that bubble had burst, leaving Smith humiliated and mired in debt for the rest of his life. During the Quasi-War* with France, George Washington forwarded William Stephens Smith as a candidate for the post of Adjutant General of the Provisional Army. Citing his bankruptcy, Secretary of State Timothy Pickering** successfully lobbied senators to vote against Smith’s commission and the best that President John Adams could offer his son-in-law was no more than a lieutenant colonelcy and command of a regiment.

* The Quasi-War, which at the time was also known as "The Undeclared War with France," the "Pirate Wars," and the "Half War," was an undeclared naval war between the United States and France. The conflict lasted between 1798 and 1800, and was a formative moment for the United States. Although it occurred during John Adams’ presidency, the Quasi War involved George Washington.

** Timothy Pickering (July 17, 1745 – January 29, 1829) was the third United States Secretary of State under Presidents George Washington and John Adams. He also represented Massachusetts in both houses of Congress as a member of the Federalist Party. In 1795, he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society. As Secretary of State, Pickering favored close relations with Britain. President Adams dismissed him in 1800 due to Pickering's opposition to peace with France during the Quasi-War. During the War of 1812, he became a leader of the New England secession movement and helped organize the Hartford Convention. The fallout from the convention ended Pickering's political career. He lived as a farmer in Salem until his death in 1829.

****Beginning in the 17th century, people liked to prefix mar- to nouns to create a term for someone who mars, or spoils, something. A mar-joy was bad enough, but even worse was a mar-all. Although today the word plot often carries an implication of secrecy or ill intent, the "plot" used in the formation of "marplot" simply meant "a plan for the accomplishment of something." A marplot, therefore, can really mess up a perfectly good thing. The word may not have been invented by English playwright Susannah Centlivre, but it first surfaces in print in her 1709 play The Busy Body. That title refers to a character named Marplot, who misguidedly gets in the way of the lovers in the play.

Samuel Allyne Otis (November 24, 1740 – April 22, 1814) was an American politician who was the first Secretary of the United States Senate, serving for its first 25 years. He also served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives and was a delegate to the Confederation Congress in 1787 and 1788.

The obvious candidate was dapper 60-year-old Charles Thomson, secretary of the soon-to-expire Continental Congress during its entire 15-year existence. But Thomson weakened his candidacy by telling friends that he had a different secretarial post in mind—one in George Washington's cabinet.

Consequently, he decided he would indeed like to become the first secretary of the Senate—as well as secretary of the House and secretary of the entire government. This would not be too taxing, he thought, because he expected to have an assistant who would "do the ordinary business of the [Senate], so that I may not be under the necessity of attending except on special occasions and when the great business of the Nation is under deliberation." This expression of Thomson's lofty self-importance helps explain why he had attracted a more-than-usual number of enemies during his public career.

A group of those foes devised a scheme—disguised as an honor—to get him out of town during the crucial last-minute maneuvering leading to the secretary's election. Congressional leaders asked Thomson to travel from the nation's temporary New York City capital to Virginia to "notify" George Washington of his election and accompany the president-elect back to New York. Washington needed no notification, but he accepted Thomson's companionship in good humor. With Thomson safely away from the Senate, Vice President-elect John Adams maneuvered for the election of his own candidate—Samuel Allyne Otis.

Supremely qualified for the job, the 48-year-old Otis had been a former quartermaster of the Continental army, speaker of the Massachusetts house of representatives, member of Congress under the Articles of Confederation, and John Adams' long-term ally. On April 8, 1789, two days after the Senate achieved its first quorum, members elected Otis as their chief legislative, financial, and administrative officer.

[Thomson aspired to be confirmed as Secretary of the newly constituted U.S. Congress or to be appointed Secretary of the Senate, but, having failed to gain that appointment — Samuel Allyne Otis was instead appointed Secretary of the Senate on April 8, 1789 — Thomson relinquished his commission and handed over the Great Seal of the United States and his official papers to the United States Department of Foreign Affairs (the precursor of the United States Department of State) on July 23, 1789.]

Otis' early duties combined symbolism and substance. On April 30, he had the high honor of holding the Bible as George Washington took his presidential oath of office. Throughout that first session, which lasted until September, Otis tirelessly engaged the many tasks associated with establishing a new institution. As the Senate set down its legislative procedures and carefully negotiated relations with the House and President Washington, Otis became a key player.

Others noticed and several coveted his increasingly influential job. Among the contenders was William Jackson, a secretary to President Washington. Jackson asked Washington to advance his prospects by removing Otis from the scene—through an appointment to a federal post in Massachusetts. Washington failed to cooperate, perhaps thinking that John Adams might view this as executive meddling in legislative affairs. From 1789 to 1801—the period of Adams' eight years as vice president, and four as president—Otis enjoyed great job security. The situation changed in 1801. The electoral "Revolution of 1800," which shifted control of Congress and the presidency from the Adams Federalists to the Jeffersonian Republicans, gave Otis reason to begin checking his retirement options. When John Quincy Adams became a senator in 1803, he reported to his father that Otis "is much alarmed at the prospect of being removed from office. It has been signified to him that in order to retain it, he must have all the [Senate's] printing done by [William] Duane [editor of an anti-Adams newspaper]. His compliance may possibly preserve him one session longer." The Senate subsequently awarded Duane the lucrative contract.

Through the considerable political turbulence between 1800 and 1814, Samuel Otis held on as secretary. But with the passing years, Otis appeared to some as less vigorous in attending to his duties. Senators complained that the Senate Journal was not being kept up to date, official communications not recorded in a timely way, and records kept in a "blind confused manner." But no one actively moved to replace him. Like Continental Congress secretary Charles Thomson, Otis had become the body's institutional memory at a time of great turnover among members.

When the 73-year-old Otis died on April 22, 1814, having not missed a single day's work in 25 years, senators seemed truly to lament his passing. The stability that he brought to the office endured well into the 19th century. His successor, former New Hampshire senator Charles Cutts, served for 11 years. Cutts' successor, former Pennsylvania senator Walter Lowrie, held the post from 1825 to 1836, followed by Asbury Dickins, who came within six months of breaking Otis' still-standing quarter-century service record. When Dickins retired in 1861 at age 80, the Senate voted him an additional year's salary, using language that would been equally fitting to Otis—"an old and faithful servant of the Senate

Former Columbia J School Dean Nicholas Lemann on Changing the Press Clause

Published: Oct. 7, 2024

FAW: You argue that “there may now be another and more pressing reason for trying to give greater legal meaning to the First Amendment’s press clause: it might function as one of a number of tools for combating the economic calamity that has befallen the organized, reportorial press in the twenty-first century, mainly as a result of the rise of the internet.” Can you tell me more about this? How would greater legal meaning of the press clause combat its economic decline?

NL: First of all, there isn’t a lot of law associated with the press clause. There wasn’t a lot of First Amendment law at all until a couple of decades into the 20th century, and 100 years roughly ago, and when there started to be, it treated speech and press as pretty indistinguishable, and the tradition focuses heavily on speech, or on press as a form of speech. So, the main area where I’ve seen journalists argue for a kind of special privilege under the press clause has been in arguing for shield laws protecting the relationship between journalists and their sources from grand jury summons and requirements to testify and things like that. These laws exist in some form in a lot of states, I think most states, but they’ve repeatedly failed to pass in Congress. And also some attempts from years ago to have the Supreme Court discern in the First Amendment itself this kind of source protection hasn’t been successful. So it’s just kind of sitting there, at least at the federal government level, as something the press wants. To my knowledge, that’s been the dominant request coming out of journalism for more robust understanding of the press clause, as opposed to the press clause and speech clause taken together.

What I’m suggesting is a professionalization of our understanding of what it means to be a journalist, something that our country has really resisted — and for reasons I understand — and that this could be used as a lever to get non-pure market funding, either from philanthropy or some form of direct or indirect government funding into news organizations. The problem for the press clause, including in these source protection efforts, has been that you can’t figure out who is and isn’t a journalist, because anybody who says they’re a journalist is a journalist. So this would be creating a way of making a more distinguishable category of who’s a professional journalist. I’m not against source protection, but that wouldn’t be the big cause for me as a journalist, the big cause would be to try to use that as a way to get special economic treatment to journalists, because I think we need that at this point.

FAW: If we saw a rejuvenated press clause emerge again in the future, what exactly would flow from that? What additional rights or privileges would the press enjoy? You mention public funding of journalism. Could you be a bit more specific on why public funding could be dependent on a more robust reading of the press clause?

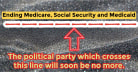

NL: I’m not as obsessed as many of my colleagues are with shield laws. I think they’re a good idea, but to my mind, given the situation in journalism now, they’re of secondary, not primary, importance. So I think it would be very difficult once there were some kind of policy enabling of certain kinds of journalism, it would be helpful to deal with the cacophony of voices of everybody and their brother saying “I’m a journalist, no, I’m a journalist, no, I’m journalist, no, I’m a journalist.” One thing that most of my colleagues would not be into, but I’m starting to play with, at least in my mind, is to have some kind of licensing procedure that requires certain kinds of education or training, and then only if you were licensed would you get these benefits. So if I’m not a licensed doctor with a medical degree, I can’t receive Medicare reimbursements, right? So, I do think there’s a connection potentially between having a constitutionally embedded legal definition of who is press versus who is a speaker as a way of building a support system around the press, as opposed to speech, which really only needs to be left alone, as far as I can tell.

FROM THE HEARTS AND JUDGMENT OF AN HONEST AND ENLIGHTENED PEOPLE

“Can authority be more amiable and respectable when it descends from accidents or institutions established in remote antiquity, than when it springs fresh from the hearts and judgment of an honest and enlightened people? It is the people only that are represented; it is their power and majesty that is reflected, and only for their good, in every legitimate government, under whatever form it may appear.”

— J. Adams.

Well I hope it was not too confusing to slug through. I have a better idea of the sedition act and it might appear that John Adams was talked into it a bit. Trump will require no encouragement in his designs.

207th Posting, October 13, 2024.