THERE IS BUT LITTLE VIRTUE IN THE ACTION OF MASSES OF MEN

On Henry Thoreau’s famous writing and of his time - Mexican-American War.

THERE IS BUT LITTLE VIRTUE IN THE ACTION OF MASSES OF MEN

This November it might seem that the masses might cause trouble again,

How Trump and some are probably counting on it to happen,

Even though many expect it and are prepared - it could happen again,

Reactionaries are still plentiful - full of disinformation and delusions,

Even though it could quickly fall flat again - they’re probably determined.

Indeed it might seem that such foolishness shouldn’t happen here,

So the crazy will probably visit us again - our own mentally ill MAGA.

Basically being around insanity for about a month doesn’t quell my angst,

Until today - I hadn’t heard speaking in tongues at the dinner table,

Trump’s disorder has caught ahold I fear - there’s no telling what will be.

Likely someone will get hurt - hopefully it will end up being MAGA,

Indeed Trump wishes to sow as much chaos as his damaged brain allows,

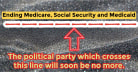

Trump cult followers are going to have a very difficult time it seems,

To the sane among us - we have a hard time rationalizing the irrational,

Let’s us keep our guard up after he loses again - crazy is only crazy,

Even though Thoreau talked of civil disobedience he would not imagine.

Victory will be declared regardless of the votes again - same ole shit,

In a country with some virtue - so many think they’re all crooks,

Really I’ve been in a odd sounding board for some time now,

To all that fear our country is mostly ignorant - you may be correct,

Understand that most can honestly see no difference between parties,

Even though I’m around raging anger now - I think it’s actually common.

If the mob goes psychotic when he goes down - screaming fraud,

Now what exact measures will they be willing to take against our laws?

Trump knows prison awaits him - will he fly away from us in the end,

Honestly the guy is quite unpredictable it might seem to most of us,

Every MAGA seeing him fleeing the coup - what exactly will they do?

Action - what will be their actions when he loses - it’s hard to say,

Could they finally feel whipped in their irrational worldview,

Trump would get his jollies if there was violence in his name,

Indeed he’d probably be glued to some television screen again,

Of the chance of prison time again maybe his supporters will balk,

Now my imagination gets away with me it seems at this prospect.

Only truthful talk to these potential conspirators might dissuade them,

Freedom is what they delusionally think they are losing - will they resign?

Masses of angry MAGA - we’ve seen it already once - please not again,

As who knows what conspiracy theory may consume them then,

So we have the manipulators pushing all their easy buttons,

Stupid is the only way to describe what they might possibly believe,

Errors in judgment again on a monumental scale,

So I really don’t know - my imagination is playing out scenarios.

Of the FBI - are their ears and eyes listening to the weird chatter,

For I think so - the alternative is not very reassuring.

Men are only referenced by Thoreau - but we know about MAGA women,

Each of these people are dangerous in a mob setting most certainly,

Now perhaps I’ve covered the vile possibilities enough - over and out.

THERE IS BUT LITTLE VIRTUE IN THE ACTION OF MASSES OF MEN

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817 – May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay “Civil Disobedience” (originally published as "Resistance to Civil Government"), an argument in favor of citizen disobedience against an unjust state. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government", explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Thoreau was a philosopher of nature and its relation to the human condition. In his early years he followed transcendentalism, a loose and eclectic idealist philosophy advocated by Emerson, Fuller, and Alcott. They held that an ideal spiritual state transcends, or goes beyond, the physical and empirical, and that one achieves that insight via personal intuition rather than religious doctrine. In their view, Nature is the outward sign of inward spirit, expressing the "radical correspondence of visible things and human thoughts", as Emerson wrote in Nature (1836).

ON THE DUTY OF CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

by Henry David Thoreau

1. How does it become a man to behave toward the American government today? I answer that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also.

2. All men recognize the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to and to resist the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable. But almost all say that such is not the case now. But such was the case, they think, in the Revolution of ’75. If one were to tell me that this was a bad government because it taxed certain foreign commodities brought to its ports, it is most probable that I should not make an ado about it, for I can do without them: all machines have their friction; and possibly this does enough good to counter-balance the evil. At any rate, it is a great evil to make a stir about it. But when the friction comes to have its machine, and oppression and robbery are organized, I say, let us not have such a machine any longer. 3. In other words, when a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves, and a whole country is unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army, and subject Ed to military law, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize. What makes this duty the more urgent is that fact, that the country so overrun is not our own, but ours is the invading army.

Paley, a common authority with many on moral questions, in his chapter on the “Duty of Submission to Civil Government,” resolves all civil obligation into expediency; 4. and he proceeds to say, “that so long as the interest of the whole society requires it, that is, so long as the established government cannot be resisted or changed without public inconveniency, it is the will of God that the established government be obeyed, and no longer.”—“This principle being admitted, the justice of every particular case of resistance is reduced to a computation of the quantity of the danger and grievance on the one side, and of the probability and expense of redressing it on the other.” Of this, he says, every man shall judge for himself. But Paley appears never to have contemplated those cases to which the rule of expediency does not apply, in which a people, as well as an individual, must do justice, cost what it may. If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning man, I must restore it to him though I drown myself. This, according to Paley, would be inconvenient. But he that would save his life, in such a case, shall lose it. This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.

In their practice, nations agree with Paley; but does anyone think that Massachusetts does exactly what is right at the present crisis?

“A drab of state, a cloth-o’-silver slut,

To have her train borne up, and her soul trail in the dirt.”

5. Practically speaking, the opponents to a reform in Massachusetts are not a hundred thousand politicians at the South, but a hundred thousand merchants and farmers here, who are more interested in commerce and agriculture than they are in humanity, and are not prepared to do justice to the slave and to Mexico, cost what it may. I quarrel not with far-off foes, but with those who, near at home, co-operate with, and do the bidding of those far away, and without whom the latter would be harmless. 6. We are accustomed to say, that the mass of men are unprepared; but improvement is slow, because the few are not materially wiser or better than the many. It is not so important that many should be as good as you, as that there be some absolute goodness somewhere; for that will leaven the whole lump. There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them; who, esteeming themselves children of Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets, and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing; who even postpone the question of freedom to the question of free-trade, and quietly read the prices-current along with the latest advices from Mexico, after dinner, and, it may be, fall asleep over them both. 7. What is the price-current of an honest man and patriot today? They hesitate, and they regret, and sometimes they petition; but they do nothing in earnest and with effect. They will wait, well disposed, for others to remedy the evil, that they may no longer have it to regret. At most, they give only a cheap vote, and a feeble countenance and Godspeed, to the right, as it goes by them. 8. There are nine hundred and ninety-nine patrons of virtue to one virtuous man; but it is easier to deal with the real possessor of a thing than with the temporary guardian of it.

All voting is a sort of gaming, like chequers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it, a playing with right and wrong, with moral questions; and betting naturally accompanies it. The character of the voters is not staked. 9. I cast my vote, perchance, as I think right; but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation, therefore, never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority. There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men. When the majority shall at length vote for the abolition of slavery, it will be because they are indifferent to slavery, or because there is but little slavery left to be abolished by their vote. They will then be the only slaves. Only his vote can hasten the abolition of slavery who asserts his own freedom by his vote.

10. I hear of a convention to be held at Baltimore, or elsewhere, for the selection of a candidate for the Presidency, made up chiefly of editors, and men who are politicians by profession; but I think, what is it to any independent, intelligent, and respectable man what decision they may come to, shall we not have the advantage of his wisdom and honesty, nevertheless? Can we not count upon some independent votes? 11. Are there not many individuals in the country who do not attend conventions? But no: I find that the respectable man, so called, has immediately drifted from his position, and despairs of his country, when his country has more reasons to despair of him. He forthwith adopts one of the candidates thus selected as the only available one, thus proving that he is himself available for any purposes of the demagogue. His vote is of no more worth than that of any unprincipled foreigner or hireling native, who may have been bought. Oh for a man who is a man, and, as my neighbor says, has a bone in his back which you cannot pass your hand through! Our statistics are at fault: the population has been returned too large. How many men are there to a square thousand miles in the country? Hardly one. Does not America offer any inducement for men to settle here? 12. The American has dwindled into an Odd Fellow,—one who may be known by the development of his organ of gregariousness, and a manifest lack of intellect and cheerful self-reliance; whose first and chief concern, on coming into the world, is to see that the alms-houses are in good repair; and, before yet he has lawfully donned the virile garb, to collect a fund for the support of the widows and orphans that may be; who, in short, ventures to live only by the aid of the Mutual Insurance company, which has promised to bury him decently.

13. It is not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong; he may still properly have other concerns to engage him; but it is his duty, at least, to wash his hands of it, and, if he gives it no thought longer, not to give it practically his support. If I devote myself to other pursuits and contemplations, I must first see, at least, that I do not pursue them sitting upon another man’s shoulders. I must get off him first, that he may pursue his contemplations too. 14. See what gross inconsistency is tolerated. I have heard some of my townsmen say, “I should like to have them order me out to help put down an insurrection of the slaves, or to march to Mexico,—see if I would go;” and yet these very men have each, directly by their allegiance, and so indirectly, at least, by their money, furnished a substitute. The soldier is applauded who refuses to serve in an unjust war by those who do not refuse to sustain the unjust government which makes the war; is applauded by those whose own act and authority he disregards and sets at naught; as if the State were penitent to that degree that it hired one to scourge it while it sinned, but not to that degree that it left off sinning for a moment. Thus, under the name of Order and Civil Government, we are all made at last to pay homage to and support our own meanness. After the first blush of sin, comes its indifference; and from immoral it becomes, as it were, unmoral, and not quite unnecessary to that life which we have made.

The broadest and most prevalent error requires the most disinterested virtue to sustain it. The slight reproach to which the virtue of patriotism is commonly liable, the noble are most likely to incur. 15. Those who, while they disapprove of the character and measures of a government, yield to it their allegiance and support, are undoubtedly its most conscientious supporters, and so frequently the most serious obstacles to reform. Some are petitioning the State to dissolve the Union, to disregard the requisitions of the President. Why do they not dissolve it themselves,—the union between themselves and the State,—and refuse to pay their quota into its treasury? Do not they stand in same relation to the State, that the State does to the Union? 16. And have not the same reasons prevented the State from resisting the Union, which have prevented them from resisting the State?

Of William Paley mentioned by Thoreau the following:

“RESISTANCE TO CIVIL GOVERNMENT”: Paley, a common authority with many on moral questions, in his chapter on the “Duty of Submission to Civil Government,” resolves all civil obligation into expediency; and he proceeds to say that “so long as the interest of the whole society requires it, that is, so long as the established government cannot be resisted or changed without public inconveniency, it is the will of God ... that the established government be obeyed, and no longer.... This principle being admitted, the justice of every particular case of resistance is reduced to a computation of the quantity of the danger and grievance on the one side, and of the probability and expense of redressing it on the other.” Of this, he says, every man shall judge for himself. But Paley appears never to have contemplated those cases to which the rule of expediency does not apply, in which a people, as well as an individual, must do justice, cost what it may. If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning man, I must restore it to him though I drown myself. This, according to Paley, would be inconvenient. But he that would save his life, in such a case, shall lose it. Thus people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.

WILLIAM PALEY

William Paley (July 1743 – 25 May 1805) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, which made use of the watchmaker analogy.

Smoothly as this train of argument proceeds, little of it will endure examination. The native subjects of modern states are not conscious of any stipulation with the sovereigns, of ever exercising an election whether they will be bound or not by the acts of the legislature, of any alternative being proposed to their choice, of a promise either required or given; nor do they apprehend that the validity or authority of the law depends at all upon their recognition or consent. In all stipulations, whether they be expressed or implied, private or public, formal or constructive, the parties stipulating must both possess the liberty of assent and refusal, and also be conscious of this liberty; which cannot with truth be affirmed of the subjects of civil government as government is now, or ever was, actually administered. This is a defect, which no arguments can excuse or supply: all presumptions of consent, without this consciousness, or in opposition to it, are vain and erroneous.

William Paley

Thoughts

Paley is regarded as one of the founding fathers of the theory of “utilitarianism” (the purpose of government is to ensure the greatest happiness of the greatest number of people in society) yet he is also a strong advocate of natural rights which is commonly assumed to be the opposite of utilitarianism. The explanation for this apparent contradiction lies in the fact that he thought the “end” of a political organisation was to ensure such happiness and the “means” to achieve this was the strict adherence to individuals’ natural rights to life, liberty, and property. This perspective changed in the 19th century when utilitarians like Bentham and his followers thought that utility could provide both the means and the end to achieve human happiness.

In this quotation, Paley provides one of the greatest demolition jobs of the idea that governments derive their legitimacy from having the “consent” of the people they govern. From his utilitarian perspective, whether one obeyed the dictates of an existing government was purely “expedient” - did it or did it not protect one’s life, liberty and property adequately; if not, how expensive or dangerous was it to change this government for a new, more effective one. According to the Lockean (and other) theories of consent, since there were no actual historical examples of explicit “compacts” (agreements or contracts between rulers and the ruled), theorists invented the ”fiction” that there was a “tacit or implied” contract, which Paley rejects on three grounds: a. that the convention could not agree to everything in advance of the formation of the government and that therefore there were things which existed prior to government which it cannot revoke; b. that there is usually no “opting out clause” whereby “be it (the government) ever so absurd or inconvenient” the citizen could dissolve the political agreement which now binds him; c. and finally that every violation of the compact by the government (which were frequent in his view) “releases the subject from his allegiance, and dissolves the government.” At the end of the passage quoted, Paley also makes the astute observation that some states prevent their unhappy subjects from leaving, but does not make the equally important point that today, most states prevent unhappy citizens from other states from entering their jurisdiction.

Christian apologetics (Ancient Greek: ἀπολογία, "verbal defense, speech in defense") is a branch of Christian theology that defends Christianity.

To take a closer look at Henry Thoreau’s writing above:

1. How does it become a man to behave toward the American government today? I answer that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it.

At the time of Thoreau writing this I sense some major disappointment in the trajectory of the country. Certainly the 20th Century governmental social programs were far from coming into existence. Apparently the fact that slavery was still widespread and that an unpopular war with Mexico was raging added to this disillusionment. I am not a trained historian and haven’t read enough about this time to get an accurate sense of the frustrations which Thoreau was feeling with the government. The idea of civil disobedience in the time of Trump and widespread assault rifles is not reassuring to me. What would Thoreau say in these times?

2. All men recognize the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to and to resist the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable.

At this time I see the possibility of the moderates and most liberals revolting immediately should Trump regain power. In this case most likely we will have the truest of tyranny and with Trump at the helm great inefficiency as well. The propagandized far right imagine tyranny currently and as “grade A” haters of government they would proclaim that the receive nothing benificial with their tax dollars. So I would guess that justification for revolution will come fairly easy. Perhaps only fear of consequences may dampen it? It’s interesting to note that in Trump’s ramblings he has suggested once again some kind of war against Mexico. Most likely such a thing would be highly unpopular again.

3. In other words, when a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves, and a whole country is unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army, and subjected to military law, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize. What makes this duty the more urgent is that fact, that the country so overrun is not our own, but ours is the invading army.

The hypocrisy of the slave in a “free country” certainly made a strong impression on Thoreau. I think Thoreau was referring to the slave patrols in reference “ours is the invading army.” That such “military law” was so present at the time is quite unlike our time it might seem. It might seem that Trump’s proposal to deport millions of Latinos might imply that such a military society may once again grace our country. One might infer the unpopular notion of such an idea from Thoreau’s writing. Trump has sworn to go after the press and “Marxist” liberals as well. Such talk should disqualify him for any office, but we live in very strange times.

4. …and he proceeds to say, “that so long as the interest of the whole society requires it, that is, so long as the established government cannot be resisted or changed without public inconveniency, it is the will of God that the established government be obeyed, and no longer.”—“This principle being admitted, the justice of every particular case of resistance is reduced to a computation of the quantity of the danger and grievance on the one side, and of the probability and expense of redressing it on the other.”

Thoreau is referring to the Christian apologist William Paley’s philosophy on government in the quotes above. Paley surely was advocating for the government to take on the veneer of God in its workings and possible oppression. This obviously disturbed Thoreau’s sensibilities that government and God were somehow divinely linked regardless of the government’s actions. As for myself, I too distrust any association with religiousity and governance. It’s obvious that they be separate for the system to have a chance in working. We have our Christian nationalists now once again trying to bludgeon the government into this very same idea. The probability of such a system actually working in a manner of personal liberty are very slim in my opinion. We don’t have to try this.

5. Practically speaking, the opponents to a reform in Massachusetts are not a hundred thousand politicians at the South, but a hundred thousand merchants and farmers here, who are more interested in commerce and agriculture than they are in humanity, and are not prepared to do justice to the slave and to Mexico, cost what it may.

We still have our merchants and farmers more interested in commerce and agriculture than of a free society. With the farmers and ranchers today, most who are leaning Republican, the thoughts of justice to the Latino migrants entering the country really doesn’t register to most of them. That is even with them depending upon the cheap farm labor they might supply which directly benefits the agriculturist. Perhaps times have not significantly changed in this regard.

6. We are accustomed to say, that the mass of men are unprepared; but improvement is slow, because the few are not materially wiser or better than the many. It is not so important that many should be as good as you, as that there be some absolute goodness somewhere; for that will leaven the whole lump.

It might seem that many who are not led by someone good are destined to not materially get any wiser on their own. The majority of Americans are warming up to the leadership of Harris and Walz. I would contend that they might just supply the goodness in leaven for the whole lump of us looking for leadership. Do they represent “absolute goodness”? My impression is that they both do. Trump on the other hand has no goodness to leaven anything. That is quite apparent to anyone who can accept reality.

7. What is the price-current of an honest man and patriot today? They hesitate, and they regret, and sometimes they petition; but they do nothing in earnest and with effect. They will wait, well disposed, for others to remedy the evil, that they may no longer have it to regret.

I might argue that this description above may have been true up until Trump. Most were willing to wait for others to right any wrongs that besieged us. I think Trump has awakened most of us to initiate action in each of our own ways. I’m not sure what exactly the “price-current” for our honesty and actual patriotism is. But it might seem that in the disaster which is Trump we’ve mostly found our price.

8. There are nine hundred and ninety-nine patrons of virtue to one virtuous man; but it is easier to deal with the real possessor of a thing than with the temporary guardian of it.

An obvious question arises when I read Thoreau’s writing on virtue. Am I only a temporary guardian of what I perceive as virtue? It’s hard to admit that you might fall in that ninety nine category rather than the one percent actually with virtue. My guess is that the percentage of virtuous might be higher than as Thoreau states here. He probably was only making a point and was not concerned with the real actual virtuous numbers. I might think that I’m mostly moral and perhaps mostly virtuous as well, but would I go out on a limb in a sticky situation dealing with country? I’m uncertain. Regardless this sentence made me think harder about my place.

9. I cast my vote, perchance, as I think right; but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation, therefore, never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority. There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men.

Casting a vote is vital in a democracy. But Thoreau accurately describes its limitations here. There has to be more to having a good government other than just voting. In the dangers which Trump poises to our nation, this certainly can never be clearer than it is now. The ballot box does present a game of chance most certainly. And “a wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance.” Thoreau is implying that the vote is only capable of so much, and at times the majority might be wrong. But it might seem that in stating this he doesn’t necessarily give a ready solution to the problem. As for myself I’m comfortable in my efforts considering my actual influence. I guess I agree with Thoreau in this statement, but like him I have no obvious solutions either.

10. I hear of a convention to be held at Baltimore, or elsewhere, for the selection of a candidate for the Presidency, made up chiefly of editors, and men who are politicians by profession; but I think, what is it to any independent, intelligent, and respectable man what decision they may come to, shall we not have the advantage of his wisdom and honesty, nevertheless?

Thoreau is criticizing the nominating process in my mind her. Editors and other politicians seemed to have the power in his mind at the convention. It might seem that the independent, intelligent and respectable man (or woman) doesn’t have a way to inject their wisdom and honesty into the process in Thoreau’s mind. This is still a problem most certainly today. But with the primaries and the process for honest seeking of the best candidate, what more realistically can we do? Was Thoreau feeling left out of the process in this writing? Somehow I think he might have.

11. Are there not many individuals in the country who do not attend conventions? But no: I find that the respectable man, so called, has immediately drifted from his position, and despairs of his country, when his country has more reasons to despair of him. He forthwith adopts one of the candidates thus selected as the only available one, thus proving that he is himself available for any purposes of the demagogue. His vote is of no more worth than that of any unprincipled foreigner or hireling native, who may have been bought.

In the twentyfirst century television and radio brings the political conventions to our homes. So nearly everyone can now watch at least. If the average viewer sees the convention drifting positions from what they may have initially supported, does the country necessarily despair of him? This seems an interesting question to ponder. Not every wish is going to be fulfilled in the process regardless realistically. Can we be swayed into the position of the demagogue? Obviously this can and does happen. I would have to say that the entirety of the Republicans are making themselves available for Trump’s purposes. And certainly Thoreau nails it here when he says “His vote is of no more worth than that of any unprincipled foreigner or hireling native, who may have been bought.”

12. The American has dwindled into an Odd Fellow,—one who may be known by the development of his organ of gregariousness, and a manifest lack of intellect and cheerful self-reliance; whose first and chief concern, on coming into the world, is to see that the alms-houses are in good repair; and, before yet he has lawfully donned the virile garb, to collect a fund for the support of the widows and orphans that may be; who, in short, ventures to live only by the aid of the Mutual Insurance company, which has promised to bury him decently.

I was somewhat curious what Thoreau might have against the Odd Fellow* organization. His description of gregariousness, a manifest lack of intellect and cheerful self-reliance was intended to perhaps describe members of this organization. I’m thinking that my mother might once have been a member so her children could go on UN tours to New York City. Self-reliance would certainly describe my late mother but neither of the other two seem to. Thoreau is perhaps describing the folks who wish to appear to be compassionate, donation willing and helpful but it may actually go against their character to do so. Thoreau was certainly sarcastic in this statement and clever.

*The order is also known as the Triple Link Fraternity, referring to the order's "Triple Links" symbol, alluding to its motto "Friendship, Love and Truth".

13. It is not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong; he may still properly have other concerns to engage him; but it is his duty, at least, to wash his hands of it, and, if he gives it no thought longer, not to give it practically his support.

I think about the overturning of Roe vs Wade. I personally think this is indeed an enormous wrong toward American women. I have other pressing concerns, such as the threat of climate change on my mind as well. I have done more than wash my hands of the anti-abortion forces. I actively post about the wrongs of it, of its expansion into more restrictions in healthcare for women. I in no way support it. I may be doing my duty on this issue, but no one has told me that explicitly.

14. See what gross inconsistency is tolerated. I have heard some of my townsmen say, “I should like to have them order me out to help put down an insurrection of the slaves, or to march to Mexico,—see if I would go;” and yet these very men have each, directly by their allegiance, and so indirectly, at least, by their money, furnished a substitute.

One could pay another to take your place in putting down a slave insurrection or march to Mexico apparently in Thoreau’s time. So this was a “gross inconsistency” in Thoreau’s eyes. Thinking about the draft during the Vietnam War, it seemed that a college deferment was in a manner buying a substitution. It certainly caused many problems in modern times. Obviously something similar happened in Thoreau’s day. Probably the same arguments were voiced as in the 1960s draft. Probably some of the hardest feelings arised from these processes.

15. Those who, while they disapprove of the character and measures of a government, yield to it their allegiance and support, are undoubtedly its most conscientious supporters, and so frequently the most serious obstacles to reform.

Reformation of government means various things to various people. Within the great wealth disparity which confronts us today, opposing views of what government should do weighs upon most according to the wealth they might hold. Low taxes and non-regulatory ideas pervade most of those people holding most of the political power now. That is primarily the most wealthy among us. Many of what's left of the middle class and lower classes generally see it mostly in another light. There are scores of Republicans who generally assist in the weathy’s cause. They continue to be a large obstacle for reform. Their allegiance is with the government bashers of all stripes, and in the process defeat their own interests in favor of the wealthy. This vicious spiral probably will not end anytime soon unfortunatly.

16. And have not the same reasons prevented the State from resisting the Union, which have prevented them from resisting the State?

It might seem that the state and federal government are much the same. Working in both I didn’t find significant differences. But the angst against the federal government seems to greatly outdo each state government in most eyes. I guess the fear that one’s taxes are going to people in the inner city somewhere through the federal government just completely irks many. I really don’t think resisting the state and federal government unequally makes a lot of sense. But it seems to happen most frequently.

Henry Thoreau mentioned the Mexican - American War numerous times. I’m my genealogy studies I found mention of my Great Grandfather’s older brother who fought in this war apparently for about a year before being listed as a deserter. I found this extremely interesting but the story probably is lost as mention of such wouldn’t bring any pride. But in any case I wanted to know what the president at that time may have said about the war. In this December 1848 Annual Message to Congress he talked a lot about it. It would seem he was proud of it all. However as is found in the Wikipedia entry - “The victory and territorial expansion Polk envisioned inspired patriotism among some sections of the United States, but the war and treaty drew fierce criticism for the casualties, monetary cost, and heavy-handedness.” It might seem that there were more critics than just Thoreau at the time. I’ve included part of Polks speech for you to gain a flavor of it.

JAMES K. POLK PRESIDENCY

December 5, 1848: Fourth Annual Message to Congress

The great republican maxim, so deeply engraven on the hearts of our people, that the will of the majority, constitutionally expressed, shall prevail, is our sure safeguard against force and violence. It is a subject of just pride that our fame and character as a nation continue rapidly to advance in the estimation of the civilized world.

To our wise and free institutions it is to be attributed that while other nations have achieved glory at the price of the suffering, distress, and impoverishment of their people, we have won our honorable position in the midst of an uninterrupted prosperity and of an increasing individual comfort and happiness.

The war with Mexico has demonstrated not only the ability of the Government to organize a numerous army upon a sudden call, but also to provide it with all the munitions and necessary supplies with dispatch, convenience, and ease, and to direct its operations with efficiency. The strength of our institutions has not only been displayed in the valor and skill of our troops engaged in active service in the field, but in the organization of those executive branches which were charged with the general direction and conduct of the war.

The war with Mexico has thus fully developed the capacity of republican governments to prosecute successfully a just and necessary foreign war with all the vigor usually attributed to more arbitrary forms of government. It has been usual for writers on public law to impute to republics a want of that unity, concentration of purpose, and vigor of execution which are generally admitted to belong to the monarchical and aristocratic forms; and this feature of popular government has been supposed to display itself more particularly in the conduct of a war carried on in an enemy's territory.

The war with Mexico has developed most strikingly and conspicuously another feature in our institutions. It is that without cost to the Government or danger to our liberties we have in the bosom of our society of freemen, available in a just and necessary war, virtually a standing army of 2,000,000 armed citizen soldiers, such as fought the battles of Mexico.

In my research I found mention of a Mexican Officer, Ramón Isaac Alcaraz, who wrote widely about the Mexican-American conflict. And an American officer, Albert Ramsey, took time to translate one writing into English. I found it and wanted to include some of “The Other Side” today. As to the actual truth I’m uncertain but this Mexican perspective is quite interesting to me. I’m uncertain if other Mexicans may have been involved in the writing as well. I’ve included some of the background of the Mexican-American War and the aggressive nature of the “North Americans.”

NOTES

HISTORY OF THE WAR

MEXICO AND THE UNITED STATES.

WRITTEN IN MEXICO.

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH,

AND EDITED, WITH NOTES, BY

ALBERT C. RAMSEY,

COLONEL OF THE ELEVENTH UNITED STATES INFANTRY UNIT & THE WAR "WITH MEXICO.

WITH PORTRAITS OF DISTINGUISHED OFFICERS, PLANS OF BATTLES, TABLES OF FORCES, &C., &C., &;c.

NEW YORK:

JOHN AVILEY, 161 BROADWAY,

AND 13 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON.

1850

The ambition of the North Americans has not been in conformity with this. They desired from the beginning to extend their dominion in such manner as to become the absolute owners of almost all this continent. In two ways they could accomplish their ruling passion: in one by bringing under their laws and authority all America to the Isthmus of Panama; in another, in opening an overland passage to the Pacific Ocean, and making good harbors to facilitate its navigation. By this plan, establishing in some way an easy communication of a few days between both oceans, no nation could compete with them. England herself might show her strength before yielding the field to her fortunate rival, and the mistress of the commercial world might for a while be delayed in touching the point of greatness to which she aspires.

In the short space of some three quarters of a century events have verified the existence of these schemes and their rapid development. The North American Republic has already absorbed territories pertaining to Great Britain, France, Spain, and Mexico. It has employed every means to accomplish this — purchase as well as usurpation, skill as well as force, and nothing has restrained it when treating of territorial acquisition. Louisiana, the Floridas, Oregon, and Texas, have successively fallen into its power. It now has secured the possession of the Californias, New Mexico, and a great part of other States and Territories of the Mexican Republic. Although we may desire to close our eyes with the assurance that these pretensions have now come to an end, and that we may enjoy peace and unmoved tranquillity for a long time, still the past history has an abundance of matter to teach us as yet existing, what has existed, the same schemes of conquest in the United States. The attempt has to he made, and we will see ourselves overwhelmed anew, sooner or later, in another or in more than one disastrous war, until the flag of the stars floats over the last span of territory which it so much covets.

The North Americans, intent on their plans of absorption, as soon as they saw themselves masters of Louisiana, spread their snare at once for the rest of the Floridas, and the province of Texas: both of which countries yet remained under the Spanish power. Then they called in requisition distinct tactics. Skill and open force supplied them with arms against a nation declining from the power and glory which had made it at one period the first in the world. At this time Spain was vinable to defend her colonies beyond the sea; for she had to employ all her resources to repel from her soil the invasion of a stranger. In fact, the situation of Spain was very favorable for the ambitious views of the Republic of Washington. Rightly appreciating the terrible crisis through which she was passing, it sent agents, spies, and emissaries, to Mexico, Venezuela, Santa Fe, and other points, to collect facts and dates, and to open a road which would then facilitate its plans. Prior to this, frequent explorations had been made to obtain geographical information and statistics. The travels of Captains Pike, Lewis, and Clarke, had contributed much to it. With this knowledge, then, of all that had gone before, there was nothing at present wanting more than a fit opportunity. The invasion of the Peninsula by the French presented a favorable time.

Thus, without Spain having given any cause for complaint, in the midst of profound peace, and without a previous declaration of war, the American authorities prepared a revolt and then" troops to march in 1810 into the district of Baton Rouge, and in 1812 into the district of Mobile, by using the same conduct which was afterwards observed in Texas. To extenuate the scandalous outrage which had been committed, the President declared that these territories belonged to them as integral parts of Louisiana.

I have seemed to use up all my storage in the above. I hope you got something of use from my effort.

205th Posting September 30, 2024